Ray Dalio’s free YouTube video “How the Economic Machine Works” is one of the most practical, straightforward, and useful guides to understanding macroeconomics. Dalio used this template to understand the macroeconomic environment for decades, and it contains key ideas such as debt, cycles, deleveraging, and depression. This is one in a series of posts that will break down and simplify his views. This article discusses deleveraging.

When the economy reaches its long-term debt peak, it goes through a deleveraging. Deleveraging is a situation where borrowers have got into excessive debt that cannot be relieved by reducing interest rates. People start spending less, incomes go down, it becomes harder to get credit, the prices of assets drop, banks face challenges, the stock market crashes, and there is an increase in social tensions.

In a deleveraging, people cut their spending and their incomes fall. Less income makes people concentrate more on debt payments than on anything else. The reduced income and increase in debt repayments make borrowers less creditworthy. Borrowers are considered too risky. They aren’t able to borrow enough money to pay off their debts. People are forced to sell their belongings to make up for the lack of money.

This rush to sell assets leads to a surplus of items for sale in the market. Consequently, the stock market crashes, the real estate market weakens, and it puts financial strain on banks. This drop in asset prices means that the borrowers have less valuable collateral to offer, making them even less creditworthy.

People feel like they are getting poorer. Credit is used up rapidly, leading to less spending, lower income, reduced wealth, and ultimately less credit available, which results in less borrowing, creating a vicious cycle.

Is a deleveraging a recession?

A deleveraging appears similar to a recession, but, there is a difference. In a recession, lowering interest rates can stimulate borrowing. However, in a deleveraging situation, borrowers have gotten themselves into excessive debt that cannot be relieved by reducing interest rates. Lowering interest rates is ineffective because they are already low and may even hit 0%.

Lenders realize that the debts are now too big to ever be fully paid back. The borrowers can no longer repay, and the value of their collateral has decreased. They are struggling with the debt and don’t want to borrow more. Lenders stop giving out loans, and borrowers stop borrowing. The problem is that the debts are too much, and a solution needs to be found.

What do you do about deleveraging?

How can we decrease the amount of debt? There are four ways to do this.

- People, businesses, and governments cut down on their spending.

- Debt levels are reduced through defaults and restructurings.

- Wealth is redistributed from the wealthy to the less fortunate.

- The central bank can print new currency.

1. Spending cuts

People, businesses, banks, and governments cut down on their expenses to pay down their debt. This is called austerity. This move is deflationary and painful. The reduced spending leads to fewer jobs and higher unemployment. It also means less income. Remember, one person’s spending is another person’s income. Therefore, reducing spending makes the burden of debt even heavier.

2. Defaults and restructurings

A borrower’s debts are a lender’s assets. For example, when you buy a phone on credit, you promise to pay the phone seller back. This promise is an asset for the phone seller. But if you don’t fulfill your promise—if you don’t pay the phone seller—then the asset (your promise) that the phone seller had is worthless. It’s like it disappeared.

Many lenders don’t want their assets to disappear. They agree to debt restructuring. Debt restructuring means that the lenders are willing to changing the terms of your debt. The lenders can agree to receive a smaller payment, extend the time for repayment, or lower the interest rate from the original agreement. Lenders would rather get some payment than no payment at all.

Just like cutting back on spending, reducing debt through defaults and restructurings is also painful and deflationary. It can lead to a decrease in income and asset values, making the debt situation worse. These factors also impact the central government, as lower incomes and less employment mean the government collects fewer taxes.

3. Wealth redistribution

The unemployed, most of them, don’t have enough money saved up and they need help from the government. Therefore, the government creates stimulus packages and also increase their spending to boost the economy. As a result, they spend more money than they are bringing in through taxes and end up with a budget deficit. Governments need to either raise taxes or borrow money to make up for this deficit.

The government raises taxes on the wealthy because the wealth is concentrated among a small percentage of the population. The rest of the people are either unemployed or have seen a decrease in their income. This move helps redistribute wealth in the economy, moving it from the ‘haves’ to the ‘have nots’. The ‘have-nots’, who are going through tough times, begin to feel anger towards the wealthy ‘haves’. The wealthy ‘haves,’ being squeezed by a struggling economy, decreasing asset values, and the rise in taxes, begin to resent the ‘have nots.’.

If the economic situation continues to decline, there is a possibility of social unrest erupting. Apart from conflicts within a country, there can also be tensions between different countries, especially between those who owe money and those who are owed money. This could lead to major political changes, which might be extreme. In the 1930s, these tensions contributed to Hitler’s coming to power, the start of a war in Europe, and a depression in the United States.

4. The central bank prints new currency.

The Central Bank has to print new currency out of thin air because, at this point, people are desperate for money. The United States printed a lot of money during the Great Depression, as well as in 2008 when the central bank—the Federal Reserve—printed over two trillion dollars. Other central banks around the world also printed a significant amount of money.

Unlike cutting spending, debt reduction, and wealth redistribution, printing new currency is inflationary and stimulative. The central bank uses the newly created money to buy financial assets and government bonds. This boosts asset prices and improves people’s creditworthiness. However, this strategy only helps people who have financial assets.

The central government can buy goods and services and give money to people, but it cannot print currency. So, the central government and the central bank must collaborate to improve the economy.

The Central Bank helps the government by buying government bonds, which is like giving the government a loan. The central government can spend more money than it receives through taxes by running a deficit. This allows for increased spending on various goods, services, stimulus programs, and unemployment benefits. As a result, both people’s incomes and government debt rise, but the overall debt burden of the economy decreases.

Currently, there is a significant level of risk. Policymakers need to balance the four ways debt burdens can decrease. To maintain stability, deflationary actions need to be balanced with inflationary actions. When this balance is reached, it can lead to excessive deleveraging.

What is a beautiful deleveraging?

A beautiful deleveraging is when debts decrease in relation to income, there is growth in the economy, and inflation is not a problem. This is done by carefully balancing spending cuts, debt reduction, wealth transfer, and printing money to maintain economic and social stability.

The Central Bank can make up for a decrease in credit by increasing the money supply by printing more money. To do this, the Central Bank needs to stimulate income growth and ensure that income growth is higher than the interest rate on outstanding debt. This means that income needs to increase more quickly than debt.

For example, if a country is reducing its debt and has a debt-to-income ratio of 100%, where the debt is the same as the country’s annual income and the interest rate on the debt is 2%, If the debt is increasing at 2% due to interest while income is only growing at 1%, the debt burden will not go down. To lower the debt burden, printing money is needed to exceed the rate of income growth compared to the rate of interest.

However, printing money can be abused easily because it is simple and people prefer it over other choices. The key is to avoid excessive printing of money to avoid causing high levels of inflation, like what happened in Germany in the 1920s. This is why policymakers must find a balance to make sure reducing debt does not become too harsh. Although growth is slow, the amount of debt decreases, leading to a positive process of reducing debt.

Lost decade

When people’s incomes begin to rise, they appear more creditworthy. Consequently, lenders are more willing to lend them. With the ability to borrow money, individuals can spend more. Debt burdens finally begin to fall. As a result, the economy begins to improve.

It typically takes about a decade or more for debt levels to drop and for economic activity to go back to normal, leading to what is known as a ‘lost decade.’

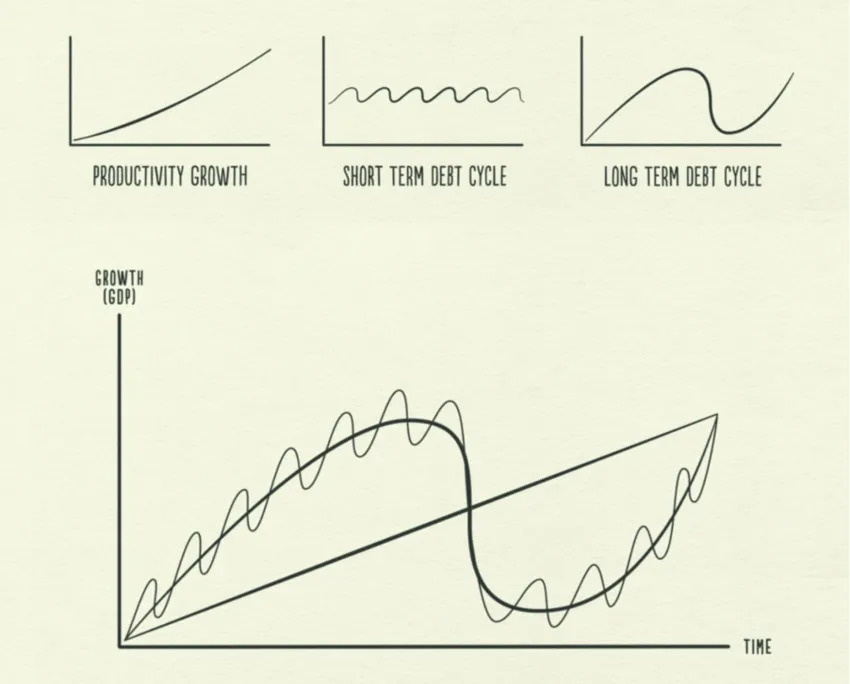

By laying the short-term debt cycle on top of the long-term debt cycle and aligning them with the productivity growth line, we can gain insight into our past, present, and where we are probably headed.

Lessons from Deleveraging

Ultimately, there are three important points to keep in mind.

- Firstly, avoid accumulating debt faster than your income, because your debt burdens will result in unmanageable financial obligations.

- Secondly, don’t have your income rise faster than your productivity, because you will eventually become uncompetitive.

- Lastly, raise your productivity level as much as you can, because that’s what matters most for long-term success.

This advice is simple, clear, and relevant for you and policymakers. Surprisingly, many people, including policymakers, overlook these factors.

Conclusion

Deleveraging is an economic process that occurs when borrowers accumulate excessive debt that cannot be alleviated through traditional means like reducing interest rates. This situation leads to a domino effect of reduced spending, lower incomes, credit challenges, asset price declines, and social tensions. Understanding the implications and strategies for managing deleveraging is crucial for economic stability.

The four key methods to address deleveraging are spending cuts, debt reduction through defaults and restructurings, wealth redistribution, and the printing of new currency by central banks. Each approach has its consequences. The first three methods have a deflationary impacts, However, the forth method, printing money has an inflationary effect. To achieve a “beautiful deleveraging”, you have to balance these tactics. This balance means that debts should decrease relative to income, economic growth is sustained, and inflation remains in check.

Policymakers must carefully navigate these strategies to prevent excessive deleveraging, maintain stability, and foster economic and social well-being. People and policymakers can mitigate the risks associated with deleveraging and pave the way for a more resilient economic future. They need to learn from past deleveraging cycles and adhere to key principles like prudent debt management.