Paper money has an intriguing history. To start off, we’ll summarize what the previous article was about. We had learnt about the history of metal money. In brief, round-shaped metal coins that were made of bronze appeared in China around 770 BC. The value of each coin was determined based on the metal it was made of. This made it easy to measure and verify the value of the coin. In 600 BC, Alyattes, who was the King of Lydia, established the very first government-controlled factory, a money mint for producing money. He made the coins by combining silver and gold. Gradually, they began to make coins out of less precious metals, mixing the expensive and cheap metals.

The Establishment of IOU Certificates

Initial international trade was done using metal coins, as coins were the only form of money back then. People found it extremely challenging to drag these heavy metal coins. So the government came up with an idea: they would let people go with a piece of paper where the amount of coins they owed was written. Thus, people could go to the Treasury and convert their pieces of paper into real coins whenever they needed them. The Kings began issuing these IOU certificates for long-distance trading. Since these papers had the king’s authentication, they were considered trustworthy, and people believed that they could exchange them for coins. Since the government spent a lot of money, these paper slips started to be circulated widely.

Merchants soon realized that these slips of paper were always accepted and could be easily exchanged for the amount of coins written on them at the capital. Why bother going through the effort of submitting them? Instead, why not exchange the paper slips with other merchants for their products? As a result, merchants started using these promissory notes, which were essentially government IOUs, as a form of currency. As the market became flooded with these IOU certificates, the need for coins decreased. Eventually, the government caught on and began printing them for use as currency. Gradually, the value of paper money was based on our belief in its worth, even though it was no longer being exchanged for physical gold and silver. And that has remained true, at least for the time being.

The Promissory Note

The Italian cities were known for their economic prowess and extensive trading activities. The Italian cities had a reputation for their economic strength and vast trading activities. They were the economic dynamos of Europe. However, they were also basically always at war. Therefore, carrying large amounts of cash was risky. To overcome this obstacle, the traders came up with a new system patterned after Chinese practices.

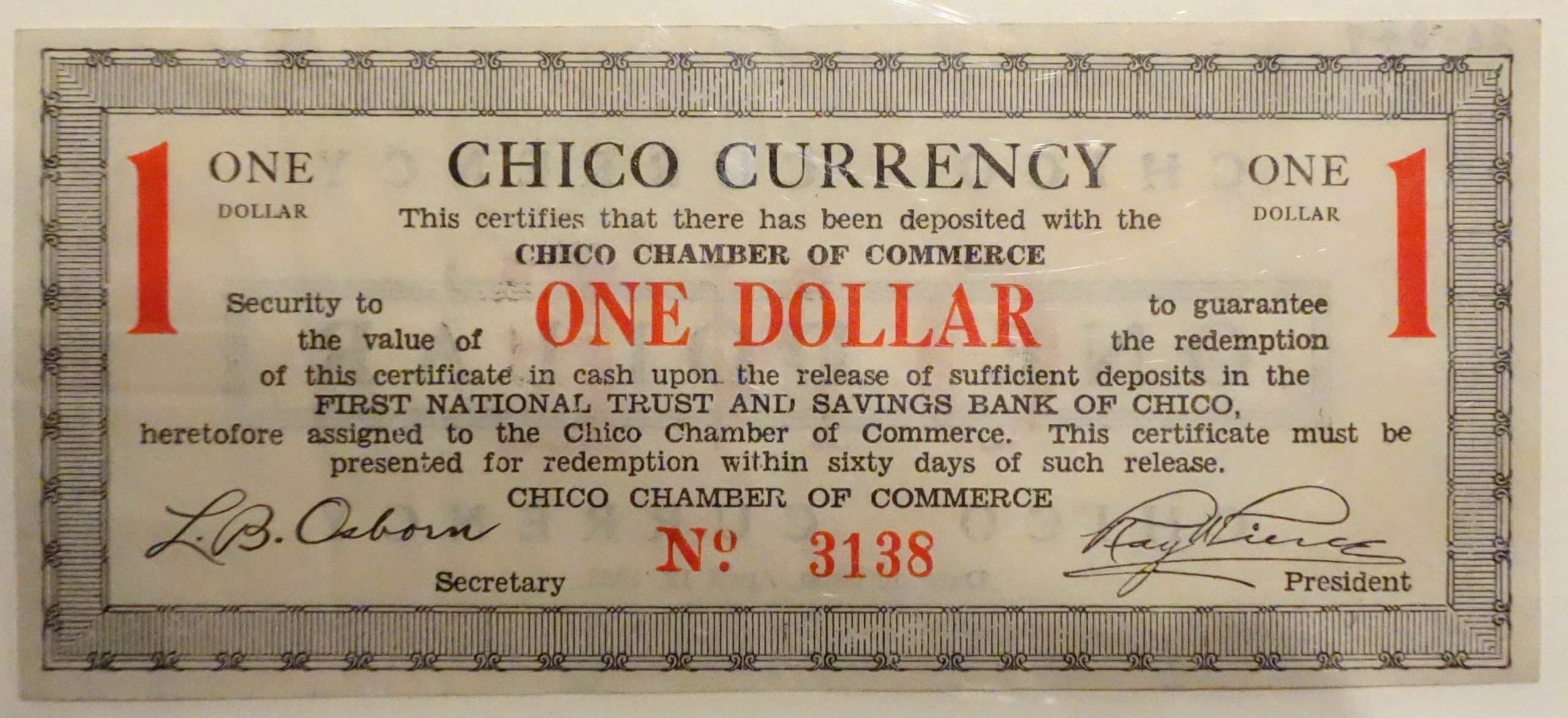

Initially, they started issuing promissory notes, which were essentially IOUs. When traders came to a new town, they would buy supplies and other goods on credit. Meaning, instead of paying in cash, they would grant the seller an IOU (I owe you), which served as the equivalent of money. The IOUs were usually secured by known and wealthy merchants who would pledge to pay off the debts on an agreed date. The twist was that the merchants never actually paid the seller directly; instead, they would settle their debts by paying a bank in their hometown.

This is how The Promissory Note would work:

The seller who sold goods would take the promissory note he received for it to the bank in his vicinity, mainly because he had access to the bank unlike most of Europe. He would take the note to the bank and exchange it for slightly less than its original value. Essentially, the bank would buy the note from him for a lower amount. After that, the bank, which had offices in other cities, sent someone with a bunch of these notes to a certain city where the notes originated. When that person landed in the town, they would take the notes to the local branch of the bank, and this branch would pay the merchant for the goods purchased. This allowed the merchant to pay for goods in a distant location by paying his local bank afterward. It was a significant advancement for commerce.

However, what would happen if the bank didn’t have a branch in the merchant’s hometown? In that case, the bank would simply sell the promissory note to another bank that had a branch there. As a result, these promissory notes began to acquire their own value. People began trading these notes, and soon the banks themselves got involved and allowed customers to take out notes directly from the bank if they had enough money deposited. However, it took quite a while for this system to fully develop.

King Charles the First

In 1640, during the reign of the unpopular Charles the First, England’s monarchy was deeply in debt. Charles disagreed with the parliament and dissolved it for over ten years. However, according to English law, only the parliament was allowed to impose taxes, which is crucial when you’re a broke king. Charles rather came up with his own unconventional and unusual schemes without involving the parliament. One of his actions was to seize all the money stored in the mint. This was a big deal. That money didn’t belong to him. Almost all of it belonged to the many merchants and goldsmiths of London. They had deposited their hard-earned money in the mint for safekeeping. The king simply took all that money and declared it to be yet another forced loan. Needless to say, his head was swiftly separated from his body.

The Role of the Merchants and Goldsmiths

In the aftermath of this action, merchants and goldsmiths joined forces. The goldsmiths suggested: “We have these humongous safes to store our gold. If you pay a small fee, you can rent a portion of the vault to store all your money.” This idea was adopted by the people. It then quickly transformed into a situation where the goldsmiths would pay a small amount of interest to people who kept their money with them in exchange for the right to lend it out. This essentially turned them into banks.

When individuals deposited their gold, these banks become the custodians of the gold. They would provide them with proof of money held in the form of a receipt, which they could later use to claim their money. Such receipts would only be redeemable by the person who made the deposit. However, the goldsmiths soon made a significant change. They started issuing receipts that could be redeemed by anyone who possessed them. This opened up the possibility for people to make and use these receipts just like they would with money. Instead of using a pile of coins to pay for something, why not deposit those coins in the bank and make transactions with these much more convenient receipts?

The Emergence of the First Semi – Official Banknotes

After these receipts began to be used commonly, people soon demanded multiple receipts in smaller denominations. For instance, you can visit a bank and exchange a 20-pound receipt for twenty-pound receipts, each worth one pound. With these, you could then use them to buy vegetables and other things. These receipts essentially became banknotes, which were the basic form of paper money.

The clever goldsmiths noticed something interesting about these banknotes: they were being passed around without always being returned to the bank. This meant that the bankers could play around with the money those notes were supposed to represent. As long as not everyone tried to turn in their banknotes at once, the bank could lend out more money than it had in its vaults. When one banknote was being redeemed, the bank was using the coin that represented it to match someone who had just converted their banknote. This gave birth to fractional reserve banking, instantly increasing the money supply in England.

Conclusion

The journey of the money from metal coins to promissory notes and then to paper money is quite intriguing. It has been driven by innovation and the necessity for certain changes in business transactions. This transition from minting and carrying heavy coins to introducing IOUs and paper banknotes significantly simplified and hastened the business processes. This was the basis of how most modern financial systems were formed. Stay tuned for the next article to find out more about the emergence of central banks and the ideology of fractional reserve banking.