This financial crisis was a period where the world experienced a significant economic downturn between 2008 and 2009. There was widespread decrease in global economies that led to a recession. Many individuals and organizations worldwide were affected, particularly millions of Americans. As financial institutions began to fail, the US government intervened by providing bailouts to prevent further collapse. It is also known as The Great Recession.

The U.S. housing market before the financial crisis

In the early 2000s, investors in the U.S. and abroad were looking for another low-risk, high-return investment. Traditionally, they invested in stocks and bonds, but these were paying very low interest. This was because Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan lowered interest rates to only 1% to keep the economy strong in the wake of the dot-com bust and the September 11, 2001, attack. But what about mortgages?

These investors started throwing their money at the U.S. housing market. They thought they could get a better return from the interest rates homeowners paid on mortgages than they could by investing in things like Treasury bonds. Also, American banks naturally did not want the money they had just lying around earning no interest, so they made it easier to get mortgages as a way to lend out cash. Americans who would normally not get home loans found it very easy to get the mortgages they needed to buy houses.

Mortgage, Mortgage broker, and Lender Relationship

If a family wants to buy or build a house, they would save for a down payment. Then they would contact a mortgage broker, who would connect the family to a lender who would give them a mortgage.

A mortgage is an agreement written on a piece of paper between the lender and a potential homeowner. They agree that the lender will loan the family hundreds of thousands of dollars to buy a house and become homeowners. In return, every month, the family has to pay back a portion of the principal, plus interest, to the lender. If they stop paying, what is called a default, whoever holds that piece of paper gets the house. Once the mortgage is approved, the broker makes a nice commission. Everything works out nicely.

Traditionally, mortgages were only for borrowers with good credit. This made mortgage debt a good investment. Mortgage lenders received regular interest payments. Also, if the borrower defaulted, they would get possession of their house. This is great for them because housing prices have been rising constantly; therefore, recovering their losses is no problem.

It was hard to get a mortgage if you had bad credit or didn’t have a steady job. Lenders didn’t want to take the risk that you might “default” on your loan. But all that started to change in the 2000s.

Mortgage-Backed Securities

The bank, the original lender, often sold that mortgage to some third party, like an investment banker, big money, or other global investors. These mortgage buyers didn’t want to just buy any mortgage; they bought mortgage-backed securities.

The investment banker would borrow millions of dollars, buy thousands of individual mortgages, and bundle them together into a nice little box. Every month, he would get the payments from the homeowners of all the mortgages in the box. He would then sell shares of that pool to investors. These shares were called mortgage-backed securities. They were simple shares of a company where every share got the same amount back.

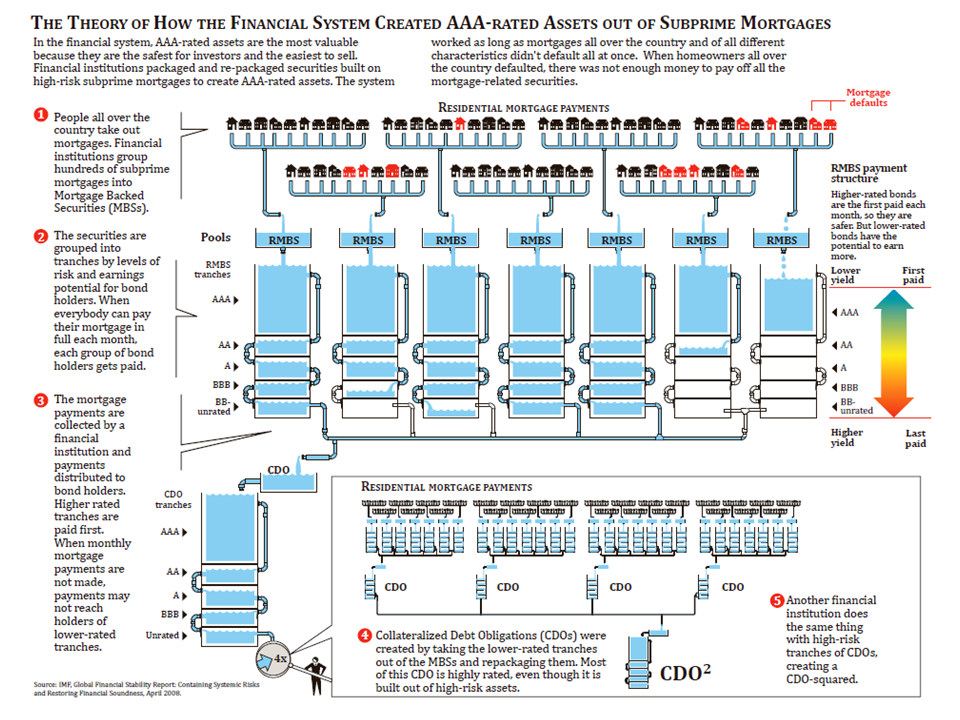

Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs)

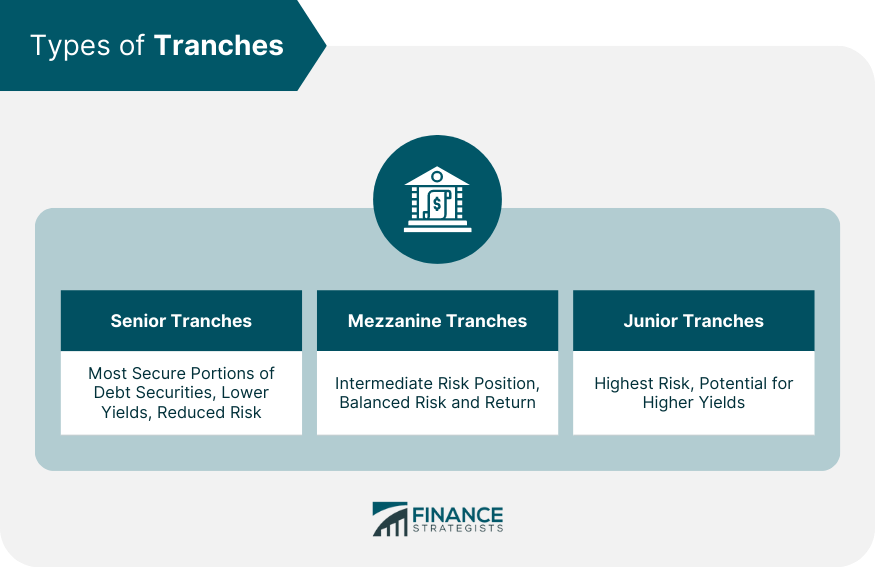

Later, the investment banker asked his banker friends to work their financial magic and cut all the mortgages in the box into three slices (shares): safe (senior tranche), okay (mezzanine tranche), and risky (junior tranche). Then, they packed the slices back up in the box as a single bond and called it a collateralized debt obligation, or CDO. CDOs are just mortgage-backed securities that have different levels of risk and different rates of return.

A CDO works like three cascading trays. As money comes in, the top tray fills first, then spills over into the middle, and whatever is left goes into the bottom. The money comes from homeowners paying off their mortgages. If some owners don’t pay and default on their mortgage, less money comes in, and the bottom tray may not get filled. This makes the bottom tray riskier and the top tray safest. To compensate for the higher risk, the bottom tray receives a higher rate of return, while the top tray receives a lower but still nice return.

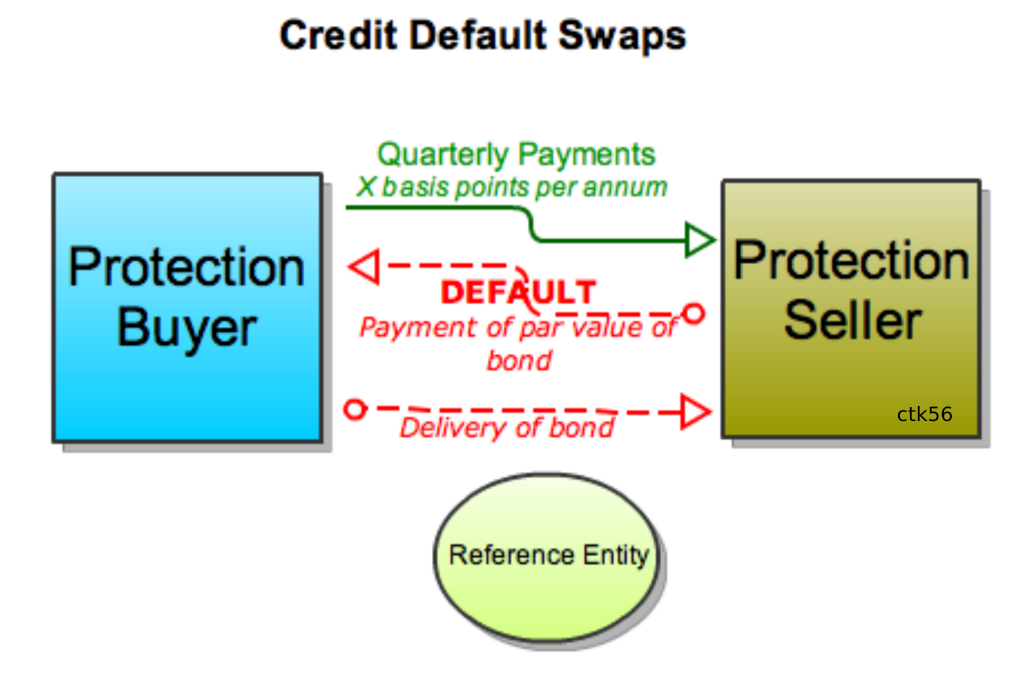

Credit default swap

The banks insured the slices through AIG for a small fee called a credit default swap to make it even safer. It swapped the bad credit rating of the CDO with the great credit rating of the big insurance company. AIG was willing to pay you off if that bond failed. So, people bought those badly rated CDO bonds from the banks. AIG loved the credit default swap, and so did the fund companies.

Credit rating agencies

The banks ensured that credit rating agencies snapped the top slice as a safe triple-A-rated investment, the highest safest rating. The okay slice was rated triple B. These agencies didn’t rate the risky slice. Because of the Triple A rating, the investment banker could sell the safe slice to investors who only want safe investments. He sold the okay slice to other bankers and the risky slice to hedge funds and other risk-takers. The investment banker made millions and then repaid his loans. Finally, the investors had found a good investment for their money, much better than the 1% Treasury bills.

Investors devoured these mortgage-backed securities. They looked like very safe bets. For one, home prices were increasing. So lenders thought, if the borrower defaulted on the mortgage, they could just sell the house for more money. House prices went up 8% in 2001. By 2004, they had gone up 14% in 2004 and 15% in 2005. So you could borrow at 1%, and you could have a house that was appreciating at 14%. This trend encouraged more people to buy bigger homes than they should have at the time. This also encouraged bankers to make more risky bets than they would have if interest rates were higher.

Subprime mortgages

The investors were so pleased that they wanted more CDOs. So the investment banker called the lender, wanting more mortgages. The lender, in turn, called the broker for more homeowners. but the broker couldn’t find anyone. Everyone who qualified for a mortgage already had one. Mortgages that were extended to responsible homeowners are called prime mortgages.

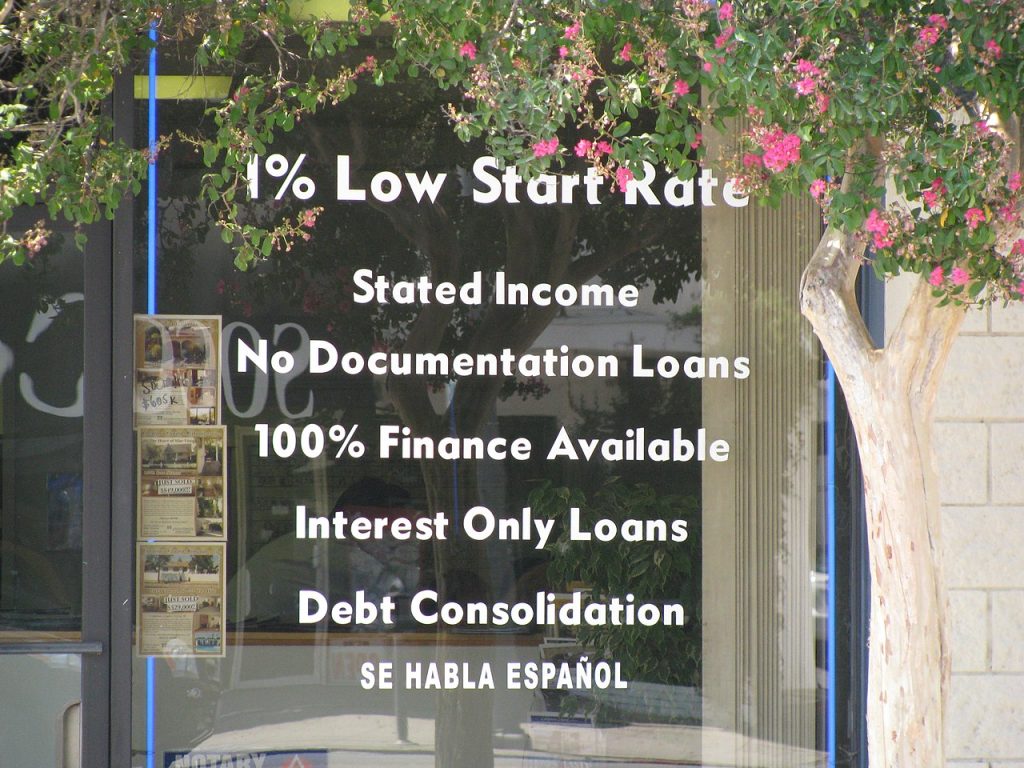

To get more mortgages, lenders loosened their standards and made loans to people with low incomes and poor credit. They argued that when homeowners default on their mortgage, the lender gets the house and sells it. By then, houses were always increasing in value. Eventually, some institutions even started using predatory lending practices to generate mortgages. They made loans without verifying income and offered absurd, adjustable-rate mortgages with payments people could afford at first but quickly ballooned beyond their means. These less-than-ideal loans were called subprime mortgages.

These new sub-prime lending practices were brand new. The credit agencies pointed to historical data that indicated mortgage debt was a safe bet. But subprime mortgages weren’t. These investments became less and less safe all the time. But investors trusted the ratings and kept pouring in their money.

The housing bubble

So, just like always, the mortgage broker connected the family with a lender and a mortgage and made his commission. The family bought a big house. The lender then sold the mortgage to the investment banker, who turned it into a CDO and sold it to the investors and others. This worked out nicely for everyone and made them all rich. No one was worried because, as soon as they sold the mortgage to the next guy, it was his problem. They didn’t care if the homeowners were to default. They were selling off their risk to the next guy and making millions.

Bubbles are rapid increases driven by irrational decisions, and they tend to burst. And this one did. Every time AIG sold another credit default swap, they made free money from the premiums being paid to them. It was almost too easy. But AIG got greedy. Normally, if an insurance company insures you for a million dollars, they should have a million in assets around to pay it, just in case. Instead of having the capital, however, AIG was relying on the statistical probability that the housing market would not fall. This strategy worked until it didn’t, and in 2007, the housing market crashed.

The housing market crash: the beginning of the financial crisis

All those subprime mortgages increased their adjustable rates and thus millions of Americans that should never have had mortgages saw their monthly repayments increase. The homeowners defaulted on their mortgage. defaulted on mortgages created an interesting problem for banks, homeowners, and AIG.

- The failed monthly payments by the homeowner turn into a house, and the bank puts it up for sale. no big deal. but more and more homeowners defaulted. Now that there were so many houses for sale on the market, there was more supply than demand. This meant that housing prices stopped rising anymore; instead, they plummeted.

- For homeowners still paying their mortgages, all the houses in their neighborhood went up for sale. Therefore, the value of their house went down. They started to wonder why they were paying back their $350,000 mortgage when the value of the house had fallen to $95,000. They decide that it doesn’t make sense to continue paying, even though they could afford to. They walked away from their house. default rates swept the country, and prices plummeted even further.

Feedback loops within housing market, financial market and economy

When those mortgages weren’t getting paid, the CDOs also started collapsing. But the banks and funds weren’t concerned yet because they had an insurance policy, the credit default swaps. The banks were relying on AIG to honor their end of the bargain. When the time came, AIG realized it had insured far too many CDOs to possibly pay up. As soon as AIG’s coffers ran dry, all the banks it had insured also started going down. The speed of the collapse was incredible: AIG ran out of money on September 15th, 2008, and later that same day, one of America’s oldest and largest banks, Lehman Brothers, was forced into bankruptcy.

The 2008 financial crisis

Now the lender tried to sell his mortgage, but the banker wouldn’t buy it. The investment banker was also holding a box full of worthless houses. He called up the investor to sell his CDO, but the investor did not want to buy. The banker tried to sell it to others, but nobody wanted to buy his bomb. The investment banker became worried because he had borrowed millions, sometimes billions, of dollars to buy that bomb, and now he couldn’t pay it back. Whatever he tried, he couldn’t get rid of these CDOs, and he was not the only one. The investors had already bought thousands of these bombs. Finally, the investor called up the homeowner and told him that his investments were worthless. That is how the crisis flowed in a cycle.

The whole financial system was frozen, and things got dark. All these bets and financial instruments resulted in an incredibly complicated web of assets, liabilities, and risks. So that when things went bad, they went bad for the entire financial system. Some major financial players declared bankruptcy, like Lehman Brothers and AIG. Others were forced into mergers or needed to be bailed out by the government. No one knew exactly how bad the balance sheets at some of these financial institutions were. These complicated, unregulated assets made it hard to tell. Panic set in. Trading and the credit markets froze. The stock market crashed. And the U.S. economy suddenly found itself in a disastrous recession.

![Chart showing feedback loops within housing market and with financial market and economy

Summary

This diagram explains two vicious cycles at the heart of the subprime mortgage crisis.

Cycle One: Housing Market

The first cycle is within the housing market. Voluntary or involuntary foreclosures increase the supply of homes, which lowers home prices creating further negative equity. By September 2008, average U.S. housing prices had declined by over 20% from their mid-2006 peak.[1][2] This major and unexpected decline in house prices means that many borrowers have zero or negative equity in their homes, meaning their homes were worth less than their mortgages. As of March 2008, an estimated 8.8 million borrowers — 10.8% of all homeowners — had negative equity in their homes, a number that is believed to have risen to 12 million by November 2008. Borrowers in this situation have an incentive to "walk away" from their mortgages and abandon their homes, even though doing so will damage their credit rating for a number of years. The reason is that unlike what is the case in most other countries, American residential mortgages are non-recourse loans; once the creditor has regained the property purchased with a mortgage in default, he has no further claim against the defaulting borrower's income or assets. As more borrowers stop paying their mortgage payments, foreclosures and the supply of homes for sale increase. This places downward pressure on housing prices, which further lowers homeowners' equity. The decline in mortgage payments also reduces the value of mortgage-backed securities, which erodes the net worth and financial health of banks. This vicious cycle is at the heart of the crisis.[3]

Cycle Two: Financial Market and Feedback into Housing Market

Foreclosures reduce the cash flowing into banks and the value of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) widely held by banks. Banks incur losses and require additional funds (“recapitalization”). If banks are not capitalized sufficiently to lend, economic activity slows and unemployment increases, which further increases foreclosures. As of August 2008, financial firms around the globe have written down their holdings of subprime related securities by US$501 billion. Mortgage defaults and provisions for future defaults caused profits at the 8533 USA depository institutions insured by the FDIC to decline from $35.2 billion in 2006 Q4 billion to $646 million in the same quarter a year later, a decline of 98%. 2007 Q4 saw the worst bank and thrift quarterly performance since 1990. In all of 2007, insured depository institutions earned approximately $100 billion, down 31% from a record profit of $145 billion in 2006. Profits declined from $35.6 billion in 2007 Q1 to $19.3 billion in 2008 Q1, a decline of 46%. Federal Reserve data indicates banks have significantly tightened lending standards throughout the crisis.[4] Unemployment in the U.S. has increased to a 14-year high as of November 2008.[5]

Further Sources and Solutions

Economist Nouriel Roubini described the vicious cycles within and across the housing market and financial markets during interviews with Charlie Rose in September and October 2008.[6] He further describes the crisis in these other video segments.[7][8] He called for an additional $250 billion to help recapitalize the banks, closure of insolvent "zombie" banks, regulatory overhaul, and $300 billion in infrastructure spending during these interviews.

References

See also

The images below contain additional high-level explanation of the crisis further citations. thumb|Factors Contributing to Housing Bubble – Diagram 1 of 2

thumb|Domino Effect As Housing Prices Declined – Diagram 2 of 2

Date 26 December 2008

Source Own work (Original text: I created this work entirely by myself.)

Author Farcaster (talk) 17:06, 26 December 2008 (UTC)

Source: Wikimedia Commons](https://helasmart.co.ke/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Subprime_crisis_-_Foreclosures__Bank_Instability.png)

The government’s response to the 2008 financial crisis

AIG was, at the time, the largest insurance company in America, with branches and offices in over 80 different countries. They had been in business since 1919 and had been declared America’s largest underwriter for insurance across many industries. In 2008, they had hundreds of billions of dollars in assets and were, in fact, well on their way to becoming the first company in the world to achieve a trillion-dollar market cap.

The Federal Reserve realized that if AIG failed, the entire world would be in trouble. Virtually all banks and insurance companies had stock and policies held by AIG. Everything was too connected. Thus, AIG was seen “too big to fail,”. The government started a program called quantitative easing; that’s where they started to buy bonds and inject cash into the economy in an attempt to save it.

The government enacted a program called the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP). This was how the government bailed out the banks. They offered 700 billion dollars of government spending to save the banking system from collapsing. It also helped stop the cascade of panic in the financial system. Automakers, AIG, and homeowners were later helped by the expansion of the relief program.

Lessons of the 2008 financial crisis

One key factor that led to the 2008 financial crisis was perverse incentives. When a policy has a negative effect, which is the opposite of what was intended, it creates a perverse incentive. Mortgage brokers got bonuses for lending out more money, but that encouraged them to make risky loans, which hurt profits in the end. That leads us to moral hazard.

A moral hazard is when one person takes on more risk because someone else bears the burden of that risk. Banks and lenders were willing to lend to subprime borrowers because they planned to sell mortgages to somebody else. Everyone thought they could pass the risk up the line. If banks know that they’re going to be bailed out by the government, they have an incentive to make risky, or perhaps unwise, bets.

The 2008 financial crisis spread blame and pain throughout the U.S. economy. The government failed to regulate and supervise the financial system. There were years of deregulation in the financial industry that made it fail. Everyone in the system was borrowing too much money and taking too much risk, from the big financial institutions to individual borrowers. The institutions were taking on huge debt loads to invest in risky assets. Many homeowners took on mortgages they couldn’t afford. Some didn’t understand what was happening. Some willfully ignored the problems. And some were simply unethical, motivated by the massive amounts of money involved.

Conclusion

Risky lending practices and complex financial instruments triggered the 2008 financial crisis, which resulted from a widespread economic downturn. These triggers led to the collapse of major institutions. The economy plunged into a deep recession. This crisis exposed the interconnectedness of the global financial system. The two key lessons that we should learn are the importance of proper regulation and oversight in the financial industry and the dangers of perverse incentives and moral hazards. They’ll help prevent similar crises in the future.